Jeep XJ. Manual - part 395

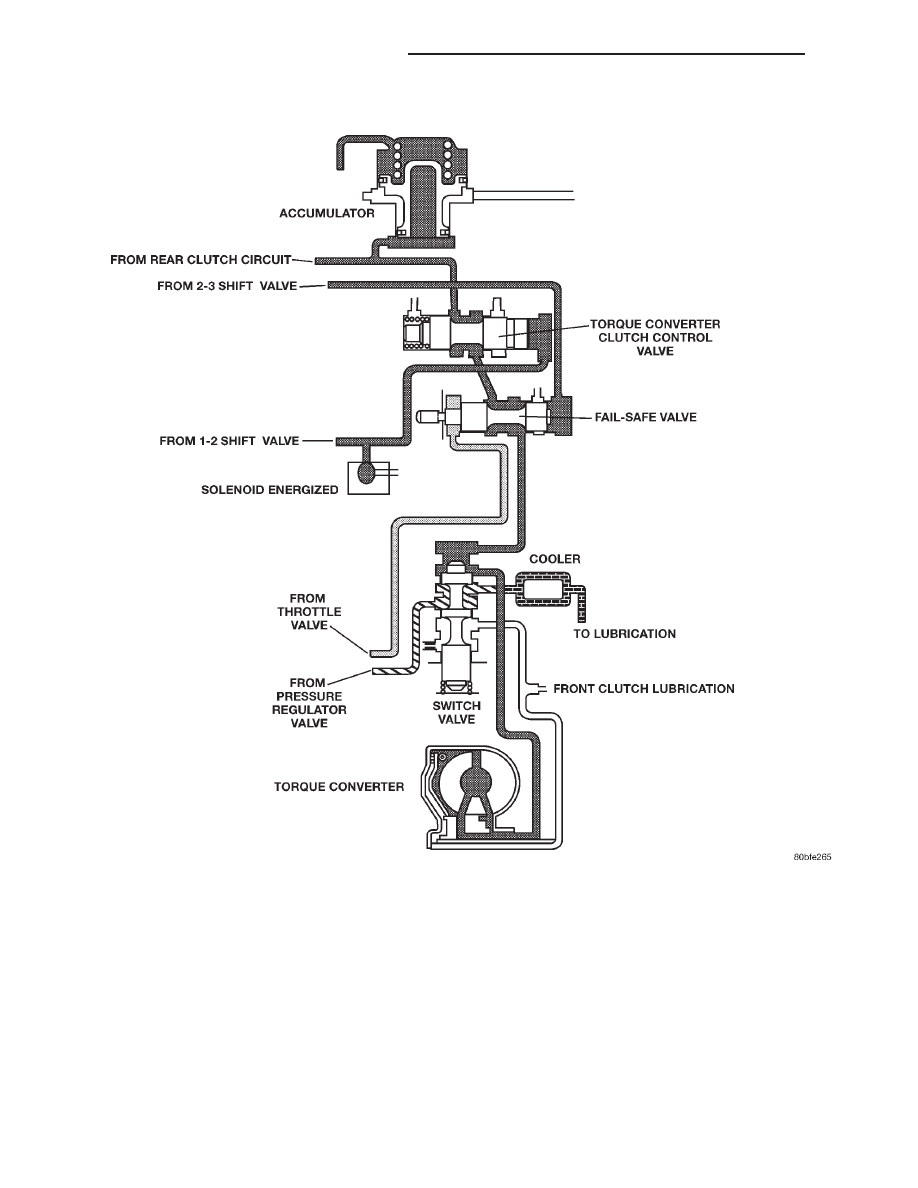

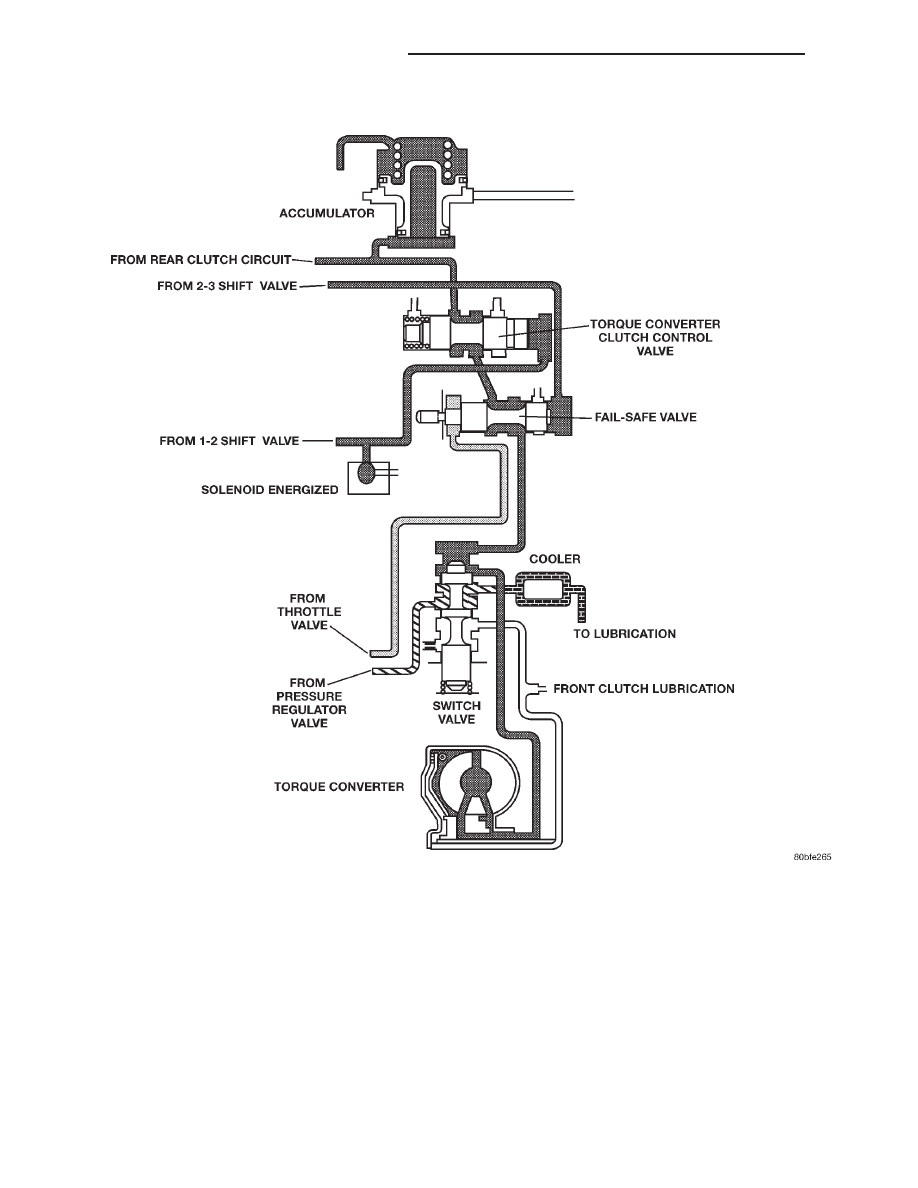

Fig. 34 Switch Valve-Torque Converter Locked

21 - 116

AUTOMATIC TRANSMISSION—30RH

XJ

DESCRIPTION AND OPERATION (Continued)

|

|

|

Fig. 34 Switch Valve-Torque Converter Locked 21 - 116 AUTOMATIC TRANSMISSION—30RH XJ DESCRIPTION AND OPERATION (Continued) |