Jaguar XJ-S. Manual - part 13

47

Jim Isbell didn’t like how much grief was required getting the plug out after it had dried up, and determined it wouldn’t

happen again. “I have cut the tabs off of the rubber plug that fills the adjustment hole for the chain tensioner. I have

made a simple aluminum “L” shaped piece that fits under a water pump bolt and holds the plug so it won't fall out.”

If desired, the opening may be plugged with a compressible rubber type freeze plug. This may even be preferable to the

original plug, since it will make a reliable airtight seal. Be sure that the plug does not interfere with the timing chain or

the operation of the tensioner.

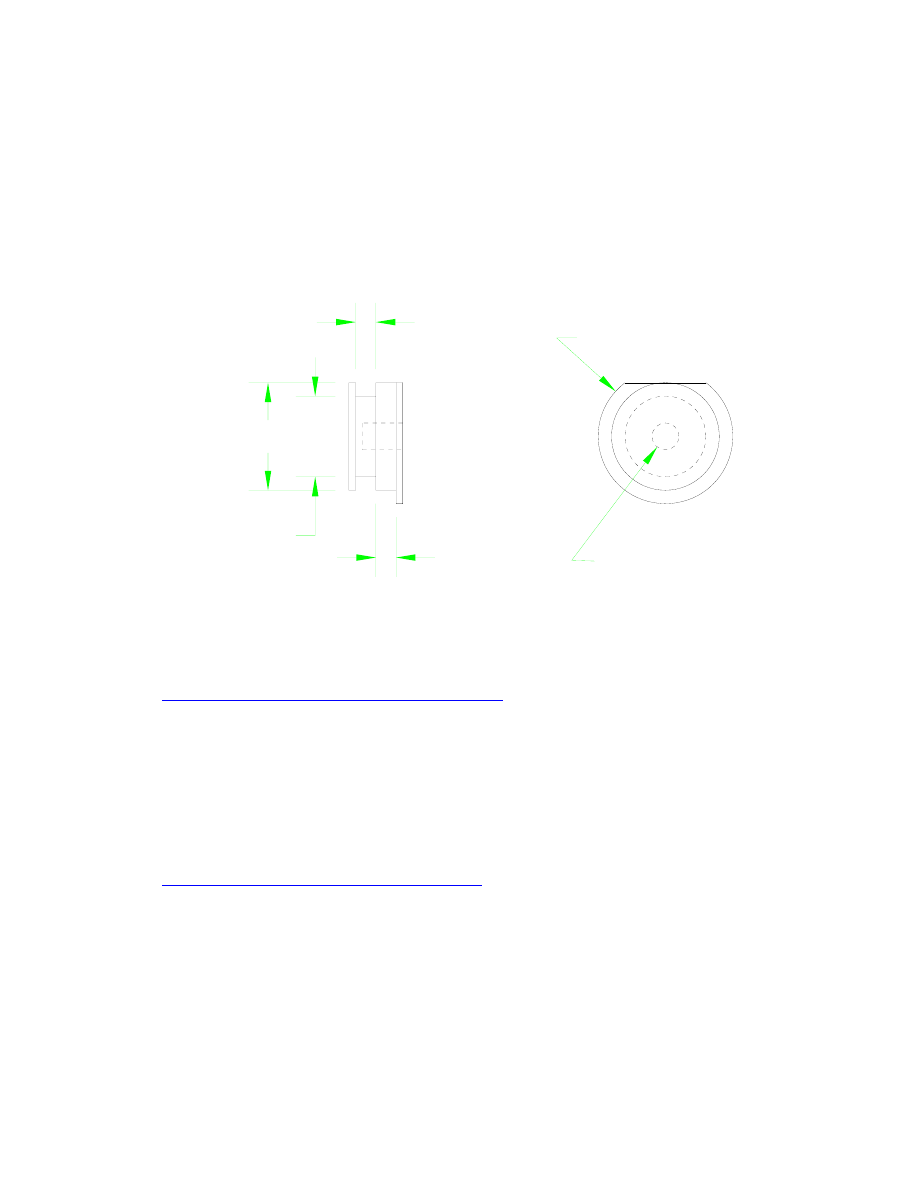

It isn’t too difficult to make an aluminum plug for this hole with provision for fitting an O-ring for sealing. Figure 2

shows a design.

8125" dia

.990" dia

1/4"-20

3/16"

3/16"

1-1/4" dia

Figure 2 - Timing Chain Tensioner Access Hole Plug

One such plug was machined by Ron Morse and successfully tested on the author’s car; you can see a picture of this

installation at

http://www.jag-lovers.org/xj-s/book/TensionerPlug.html

Note that, even though this plug fits snugly in the hole when fitted with a proper Viton O-ring (#210), it lacks any

positive retention and therefore might blow out if pressure builds in the crankcase for some reason. Since you don’t

want to lose it after paying to have it made, something similar to Isbell’s little tab under a water pump bolt is in order to

make sure it stays put. The threaded hole in the center is to aid in removal when you actually want to get it out; just

screw in a 1/4” screw and use it to pull or pry on.

If you don’t want to make your own, Ron Kelnhofer (page 716) has some for sale. His are very similar to the

illustration shown except that he has added a retention scheme, a checkball that can be engaged to grip the side of the

opening so a separate tab under a bolt head is not necessary. You can see a picture of his plug at

http://neptune.spacebears.com/cars/engr/tension.html

OIL LEAKS AT SANDWICH PLATE BOLTS: The bolts that hold the sandwich plate to the bottom of the block are

threaded into holes that open at the top to the outside of the block; if you used bolts that were too long, the ends of the

bolts would stick up through the flange and be visible from outside the engine. This arrangement was no problem with

the oil pan used on the SIII E-Type, since the bolt heads were likewise visible from outside the engine and the gasket

would seal between the pan and the block inboard of the bolt holes, so the bolts themselves would remain dry. When

the sandwich plate configuration was introduced in the XJ12 and XJ-S, however, a widened oil pan was provided at the